Year of the Blue Tarp

an ongoing project

january 1, 2024 - january 1, 2025

For 365 days, from January 1st, 2024 to January 1st, 2025, any time I see a blue tarp in the course of my daily life, I will pause and photograph that blue tarp with whatever device I have on hand.

These devices could include: disposal cameras, film cameras, iPhone cameras, digital cameras, Polaroid cameras, or any other way of taking a photograph.

I hope to allow for and value daily interruptions, especially interruptions of my daily life by beauty, and also to delight in and play with the possibilities of repetition and juxtaposition.

The photographs will be posted to this site and to Instagram to create a textile installation—a digital quilt, of sorts.

// the constraints

-

Since my childhood in the north woods of Minnesota, I've been obsessed with the utility and beauty of blue tarps.

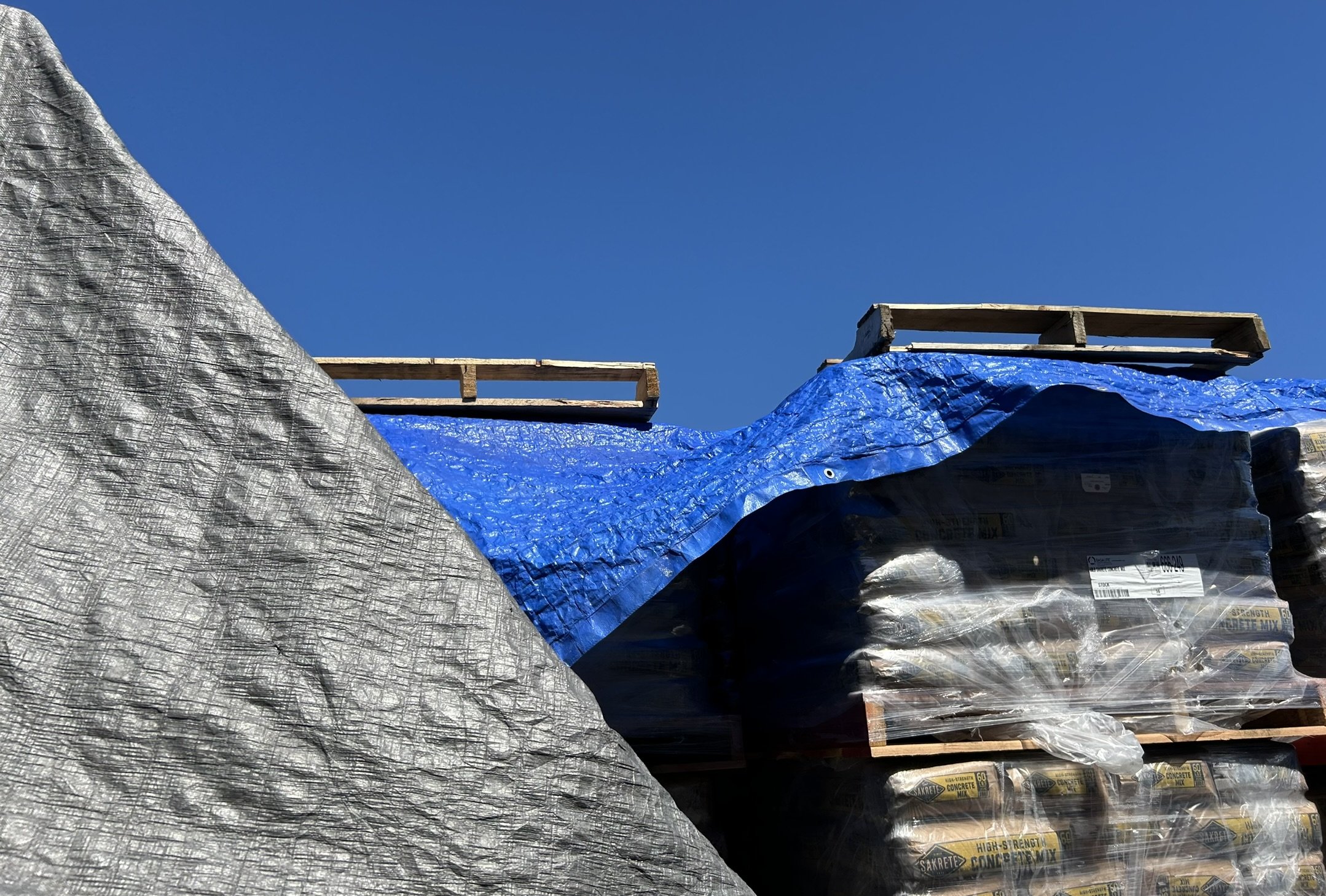

I first fell in love with their practical uses—covering wood piles, containing loaded truckbeds, giving shelter, sealing broken car windows, patching roofs, wrapping boats, hauling fallen leaves, protecting hay bales, and more—while also being taken in by the unique and vibrant hue, especially when set against the dreary greys of a north country winter.

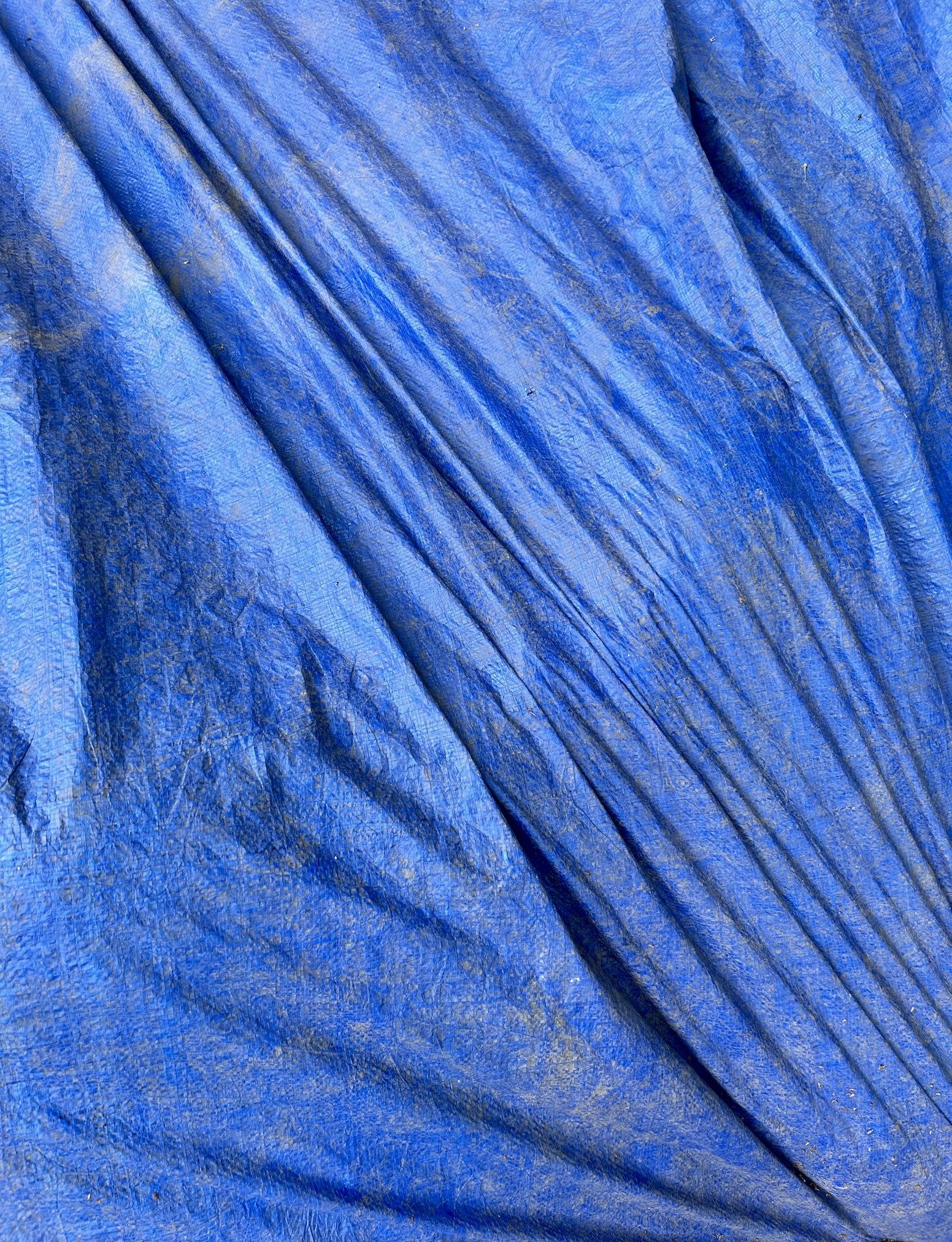

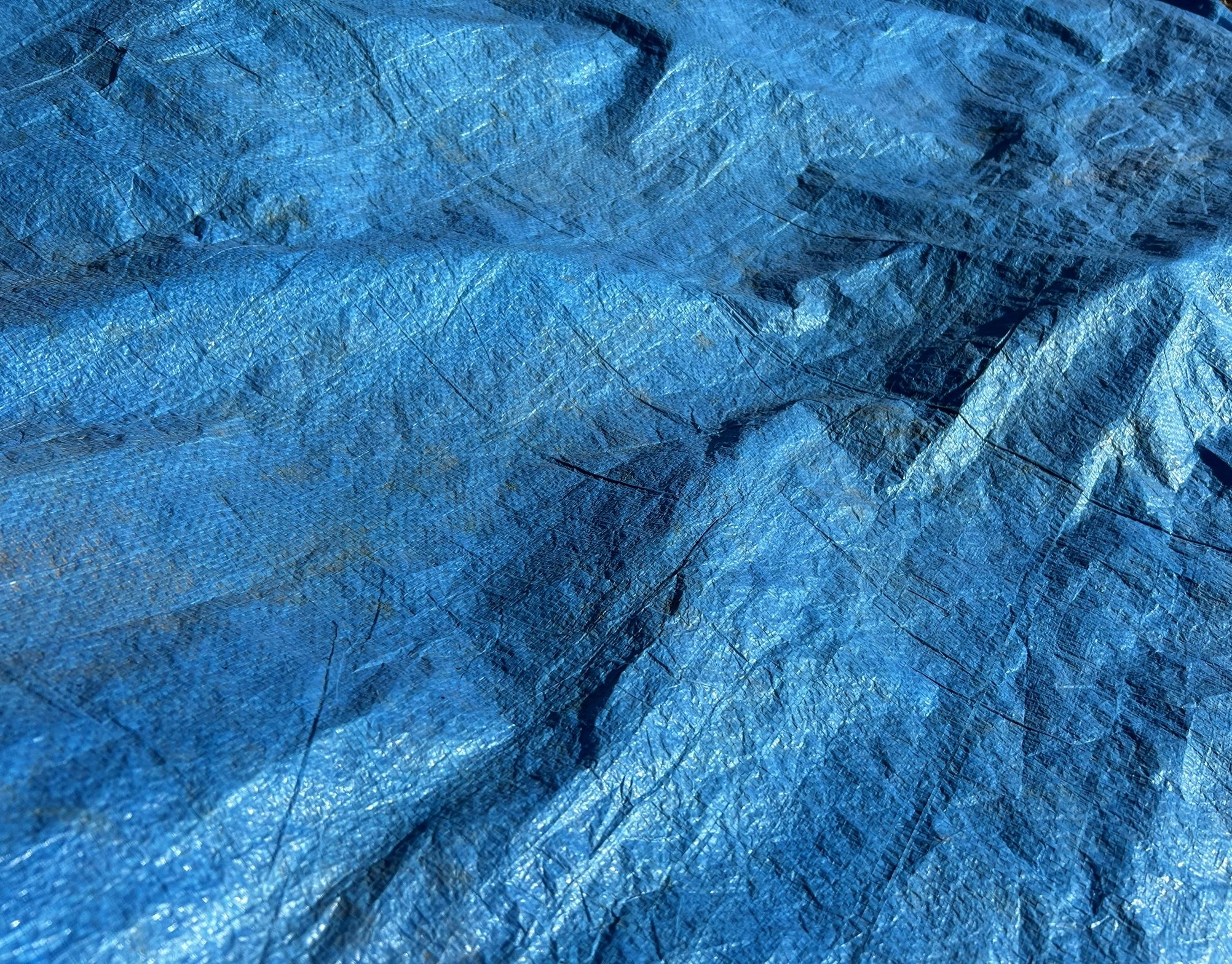

As I grew older and traveled farther, I saw blue tarps everywhere I went. I began to regard them as a ubiquitous but overlooked symbol of modernity. They reminded me, too, of home and of the kinds of physical work I have taken part in. I saw blue tarps used especially by scrappers, artisans, traders, workers, and wanderers of all kinds. It’s not lost on me, as well, how blue tarps resemble water, at times, in the ways that they can suggest waves or fluidity. Or they appear as the sky, in their expanse of surface. Lastly, since they are so frequently used to cover objects, I am drawn to the ways blue tarps create sculptural outlines, highlighting form and shape.

My obsession with blues of all kinds deepened through encounters with the music of the blues, the work of Jericho Brown, Maggie Nelson's Bluets, William Least Heat-Moon's Blue Highways, Bob Dylan’s “Tangled Up in Blue,” the research of Horace-Bénédict de Saussure, and other encounters.

This year I want to explore the tensions held within this specific textile object. I feel blue tarps hold a history and beauty that draws me to them and also they are objects that, because of their resistance to biodegradation, symbolize the overreach of human technology and our own current precarity as a species.

-

Modern tarpaulins are typically made from woven polyethylene. Polyethylene is the most commonly produced plastic.

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, a tarpaulin is:

A covering or sheet of canvas coated or impregnated with tar so as to make it waterproof, used to spread over anything to protect it from wet.

The word is generally thought to be formed from tar + pall + -ing and first appears in the writen record in 1607.

The word was also used as a nickname for a mariner or sailor, especially a common sailor.

-

In addition to taking photographs, throughout the course of the year I will research as deeply as I can the history, production, materials, textures, shapes, and qualities of blue tarps.

This could include site visits to factories, archival research, as well as artistic explorations through weaving, sculpture, poetry, and other mediums.

The extent of this research will be determined by the resources available to me, such as time and financial support. The results, findings, delights, and curiosities encountered in these explorations will be selectively posted to this site to create an ARCHIVE OF BLUE.

-

Please feel free to follow and share the project on Instagram!

If you know of any grants or sources of funding that may be helpful, please send those ideas to: peterguythepoet@gmail.com.

Thank you!

-

As I approach the halfway point of this project, I am taking a moment to pause and reflect on what I have learned so far.

So far I have seen about 100 blue tarps this year and have taken 117 photographs.

The complete set of photos is on the associated Instagram channel (@yearofthebluetarp). The gallery below is a selection.

One modification to my constraints I decided to implement early on was that I would not photograph blue tarps that are being used by unhoused people as temporary or permanent shelter. It doesn’t feel right in terms of respect and consent. While we desperately need more humane conversations about houselessness, this project is not the one to address that crisis. There is one exception, and that is the photo of Camp Nenookaasi taken shortly before the MPD cleared the encampment. I made this exception because the community was actively asking community members to document and spread awareness about the eviction.

I have found more reasons to love blue tarps.

I love the mystery they create when they are used to cover or conceal. I love that they are depended on to protect objects we value and objects we have forgotten. I love that they can catch the wind. I love that they are often in close proximity to dirt and to wood. I love that they are surfaces that hold light and shadow.

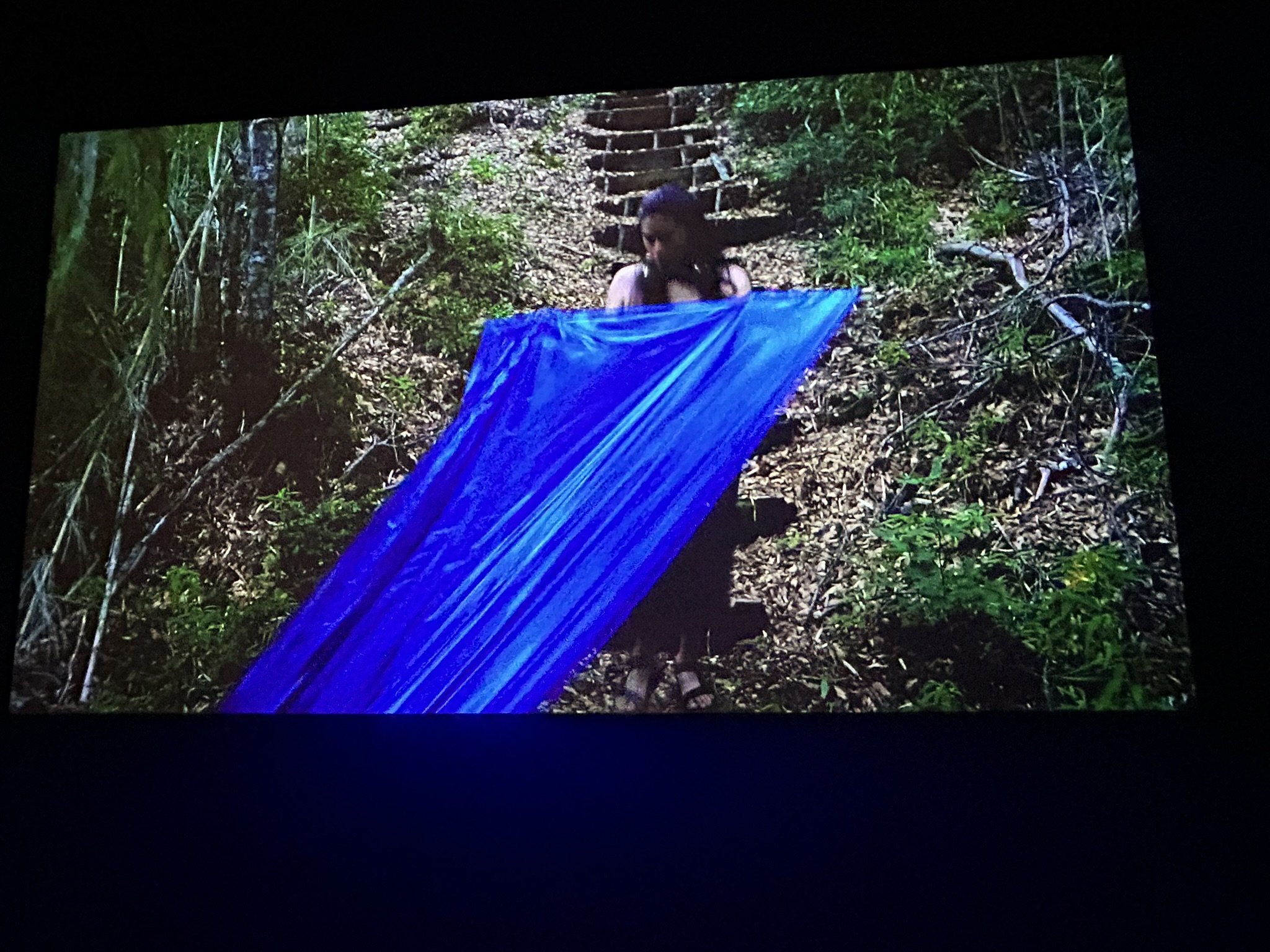

At this point, I have started to take photos of people interacting with blue tarps, experimenting with potrait and self-portrait.

-

One of the unexpected pleasures of this project has been encountering other artists who are seeing and appreciating blueness and, specifically, the blue tarp as well. I didn't expect to encounter a photographer from Brussels, a visual artist working in Mumbai, an oil painter in the Hudson Valley, an interdisciplinary artist born in San Juan and working in NYC, a Boston-based landscape painter, and a Portland photographer--to name only several--to also be drawn to the color, texture, and sculptural quality of the same material. It's exciting to learn from and feel connected to the likes of Kevin Quiles Bonilla, Sven Laurent, Magali Duzant, Kirsten Deirup, Sameer Kulavoor, and David McCarthy. It speaks to me both to the global ubiquity of plastic and the blue tarp and to the way art can spread, since the advent of social media.

Which brings me (somehwat reluctantly) to considerations of Instagram and art and some reflections this project has led me to about "amateurism" in art. The way that DIY or "underground" or "amateur" art can exist on a platform alongside work featured in, for instance, Chelsea galleries or art publications or prominent museums is still remarkable to me. I won't go so far as to fully endorse the oft uncritical, techno-utopian praise of Instagram as "democratizing" but I do think that because of its visual nature, in spite of itself and its demonstrably net negative impact, it retains a tiny sliver of potential to positively connect us. I say that, I hope, without ignoring how it is highly censored, especially with regard to images from the ongoing genocide in Palestine. I say that, too, acknowledging that I may simply be rationalizing my own use of a flawed medium. Even still, its counterparts I feel, including those also owned by Meta, have more quickly and clearly devolved into spaces that actively foment misinformation and hate and genocide (see Facebook generally but especially in Myanmar and the proliferation of Whatsapp groups everywhere) and spread fascism (see Twitter, which I refuse to call by its new erasure-laden name).

At the outset of this project, thinking only about how to share in a feasible way, I set as part of the constraints of this project a requuirement to chronologically post all the photos of blue tarps I take to Instagram in an otherwise uncurated manner, which means some are inevitably unfocused or hastily taken or flawed or "not good" in one subjective way or another. In retrospect, I'm glad I established this constraint because both the juxtaposition between "high" and "low" I mentioned above has been enjoyable as has the somewhat accidental commitment to not hide experimentation, development, process, flaws, and imperfections.

There is I think, too, a connection between the above reflections and the part of this project that became about grief after a relationship that ended once the project was in motion (blueness, to me, is one expression of grief), the loss of a relationship with someone who I loved and whose feelings and approach to art I deeply respected, valued, and learned from. This person was committed in a genuine and inspiring way to artisanship, DIY creativity, the art happening outside of the colinalist gaze of the academy or galleries or museums, and challenging, with an admirably anarchist slant, the hierarchies and systems that can define art and culture.

Among many other positive ones, there was a more complicated experience I had in this relationship that sticks in my memory. While visiting their family's second home and meeting for the first time some of their close friends, one of the conversations turned toward someone who I did not know who had recently taken up creating collages and posting them on Instagram. The gossip wasn't vicious, but it wasn't exactly generous either, and it surprised me to detect traces of contempt in the critique. It's important, I think, to pause here and note that there may have been and likely were some longstanding social dynamics at play here that I did not understand, being new to the group, and that may have completely justified the tenor and approach.

But, more to the point, I found myself reflexively expecting the person I was with to object to what I was (perhaps unfoundedly) experiencing as oddly harsh criticism considering what I had come to know of their commitment to creativity and expression as an essential human need and act that is important to all people. But no objection came. I regret staying silent myself out of deference to being new to the group and an effort to be polite. And if there had been time and space to bring it up, I'm confident I would have learned from the person I Ioved and their reflections and perspective on the moment, as I had so many times before.

Setting the complicated nuances of the social situation aside, the experience led me to an important place, to honeslty pause and reflect and to ask myself questions like: What might be the valid reasons to criticize art someone is making for themselves? What is the purpose of critique, period?

It brought me, somewhat to my surprise, to be more strongly in defense of the art all of us would like to make for any reason whatseover.

And in my own practice it recentered questions that have always been present: When is the critical voice helpful, and when does it get in the way of doing the damn thing? At what stage in the artistic process is the critical voice helpful?

It reinforced for me, as well, how incredibly social the process of critique is.

I find myself, in general, perpetually crossing the landscapes between a "pure" anarchist approach and an appreciation for what resources (especially when evenly redistributed!) and cultural structures and institutions can do for us collectively. I think I have come to accept that this is an evergreen tension // debate // paradox in artmaking, in the art world. And it's helpful for me to live and create within the shadow of this tension // debate // paradox rather than to land on a definitive answer or pick a side, so to speak.

It would be disingenuous for me not to recognize and name two experiences that shape my outlook: my upbringing in a fundamentalist Christian household that sheltered me from a broader culture and my experience as a graduate of a prestigious fine arts program. The first taught me the drawbacks to being without culture, that if all culture is hyper-local. The second exposed me to art I love and ways I've thinking I value that I don't think I would have encountered any other way than in a community of studying artists, however gatekept and problematic. I should note, too: I've been recently influenced by thinkers like Alexis Shotwell, who identify contamination and compromise as potentially productive starting places rather than conditions to completely avoid.

It's not that there's no use in imagining a different world that is without hierarchy, but that ignoring the real nature of the world we live in today reminds me too much of the conservative Evangelical impulse to neglect alleviating the real and present suffering in the world because in a distant utopia all will be made whole. The trick--for me, for now--is learning how to toggle between both modes of being--attunement to the complicated labyrinth of the present and and imaginative hope for a radically different future.

The approach I have chosen in this project is a way, I hope, to reflect that and to quietly and selectively refuse categories imposed by external authorities and to take back for myself the power to determine what is valuable or worthy of note, to create my own prestige.

---

A final note on process:

Over these months, I've learned to become more comfortable being seen as odd or aberrant, saying sentences to strangers like, "I know this may seem strange, but can I take a picture of that blue tarp?" And it's a relief that most of the time following up quickly with "It's for a photo project" relaxes initial suspicion into trust. That fact alone has restored some of my faith in the average American's appreciation, or at least tolerance, of art at a time when I feel free expression is being restricted and challenged by conservative, fascist political movements like Trumpism.

-

"Blueness is a state of mind, a habit of seeing."

Paul Gruchow, "The Blue Mountains of Minnesota"

"Well, under those historical pressures, the desire for choice in partners, the desire for romantic love, operate as a place, a space, away, for individual reclamations of the self. That is a part, maybe the largest part, certainly an important part, of the reconstruction of identity. Part of the "me" so tentatively articulated in Beloved. That's what she needs to discover. It will account for the satisfaction in the blues lyric and the blues phrase whether or not, and mostly not, the relationship flourishes. They're usually, you know, somebody's gone and not coming back or some terrible thing has happened and you'll never see this person again. Whether or not the affection is returned, whether or not the loved on reciprocated the ardor, the lover, the singer, has achieved something, accomplished something in the act of being in love. It's impossible to hear that sort of blues cry without acknowledging in it the defiance, the grandeur, the agency that frequently belies the wail of disappointed love."

Toni Morrison, "The Source of Self-Regard"

"Blue is difficult to find in the natural world, despite its ubiquitous presence as the color of the sky and of the sea; these are simply meteorological phenomenon. These deceptively stable blues are simply reflections and refractions; this amorphous characteristic adds to the possbility of blue skies and blue haze, places to get lost and to be found."

Magali Duzant, Light Blue Desire

"One loses sight of things when they fall into the blue."

Magali Duzant, Light Blue Desire

"Blue jeans originated in Genoa; denim, named for its origins in France ("de Nîmes"), was dyed with indigo for longevity and the ability to conceal stains, and was sold in droves to prospectors on the hunt for gold."

Magali Duzant, Light Blue Desire

"Blue is the color of contradictions; it is the color of royal blood, but also of the working class."

Magali Duzant, Light Blue Desire

"In northwestern Morocco, there is a town called Chefchaouen, known for its labyrinthe streets of blue-rinsed buildings. It is almost a blue tunnel of a town. Locals believe that the blue wards off mosquitoes. Otheres say it reminds inhabitants of the sky and the need to lead a spiritual life."

Magali Duzant, Light Blue Desire

"It's how a painting, real in itself, also reveals reality by connecting a blue scarf with a woman's blue eyes, for example."

Mei-Mei Berssenbrugge, A Treatise on Stars

-